Eighteen years ago the Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament, edited by D. A. Carson and G. K. Beale, was released. It was a massive work (1280 pages) by eighteen different scholars on all of the quotes and many of the allusions to the OT in the NT books. One question that I had after I got my own copy was, What about the Old Testament? At this point, I was fresh out of Bible college and had never thought much about how the NT systematically uses the OT, especially in regard to its allusions. But in what ways did books in the OT refer to other books in the OT?

Just a few years ago (2021), Gary Edward Schnittjer—Distinguished Professor of Old Testament at Cairn University—single-handedly wrote Old Testament Use of Old Testament. It is an incredible work for all who are interested in the Old Testament. (See his new How to Study the Bible’s Use of the Bible, co-authored with Matthew Harmon).

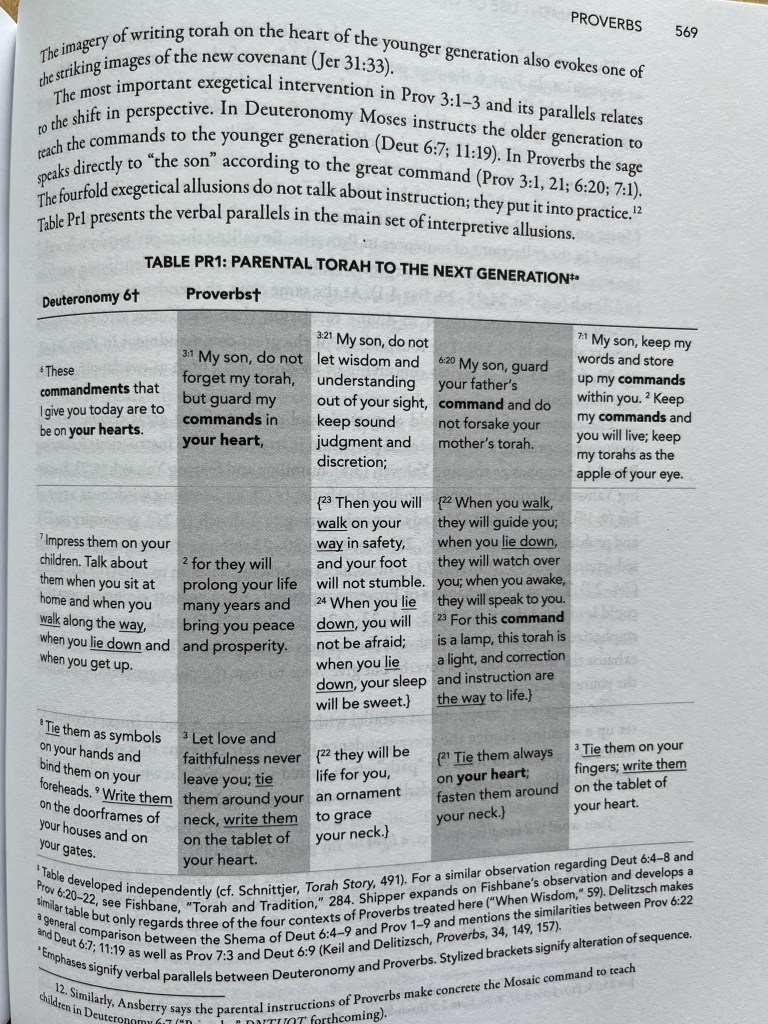

This introductory chapter addresses the complexities of studying the scriptural use of Scripture, emphasizing the challenges of responsible interpretation and exegesis. It outlines key sections, including definitions of scriptural exegesis and allusion, and discusses the importance of detecting allusions amidst competing claims. The chapter highlights the need to evaluate exegetical allusions by examining the direction of dependence and the difficulties in dating Hebrew Scriptures. It contrasts diachronic and synchronic studies, noting that their underlying goals can vary significantly. The chapter encourages patience, acknowledging the contested nature of the subject, and aims to provide a framework for evaluating evidence rather than resolving debates. A glossary is also suggested for further clarification.

Many offer methods to detect quotations, allusions, and echos, but how can we know what was actually intended by the biblical author? Schnittjer acknowledges that this type of study is subjective. Schnittjer writes, “Detecting allusions creates tension between art and science” (xxi). One can either end up in a too-mechanical ditch, while the other ends up “being too intuitive and rest[s] everything on speculative preferences” (xxi). Schnittjer has put empirical controls in place to help control subjectivity “to offer verifiable and transparent introduction” (xxi).

Every potential exegetical allusion is rated on a scale from A (very likely) to F. Level F refers to non-exegetical parallels that remain important, but “[t]hey simply do not represent exegetical allusions” (xxiii). These non-exegetical allusions are filtered out and placed into a final section called Filters. Schnittjer believes it is important to distinguish intentional allusions from coincidental phrases, and emphasizes that we carefully evaluate the verbal, syntactical, and contextual evidence. We can’t just take his words wholesale; we need to continue doing the exegetical work ourselves.

I don’t completely understand how this section works due to the example Schnittjer gives soon after this. He writes, “Care must be taken not to merely count uses of a term. Patterns of distribution and other factors need to be evaluated. Though the term “ark” (תֵּבָה) appears more than twenty times, all but one occurrence appears in Genesis 6–9 making a broad non-exegetical allusion in Exodus 2:3 highly likely” (xxiv). It would seem to me that having the only other occurrence of “ark” outside of Gen 6–9 appear in Exodus 2:3 would make this a likely exegetical allusion, perhaps continuing the pattern of death and life through water. Although perhaps I am the one stretching things.

Schnittjer also covers the direction of dependence,” knowing which texts use other texts. Schnittjer refers to the cited scriptural text as donor text and the citing scriptural text as the receptor text. For example, Lev 25:43 is the donor text and Ezek 34:4 the receptor text. Schnittjer notes, “Receptor contexts tend to disambiguate and clarify difficulties” (xxxiii). In many examples, it is basically impossible to know which text came first. The phrase “like a tree planted by the water” appears in in Jer 17:7–8 and Ps 1:2–3. But who wrote the phrase first? Psalm 1 is not a “psalm of David.” It could come from his time, but we just don’t know. In his book, Schnittjer “presumes no direction of dependence unless stated otherwise” (xxix).

Schnittjer follows the OT order in the Hebrew Bible. Each chapter begins with a list of symbols, more or less the same for each chapter. Schnitter then provides up to three lists:

- the use of OT Scripture in the particular book, (e.g., Jeremiah);

- the OT’s use of Jeremiah (places where texts from Jeremiah show up in the OT);

- the NT’s use of Jeremiah.

- Somewhere among these lists there may be a section on the book’s use of its own texts (e.g., the use of Genesis by other Genesis contexts).

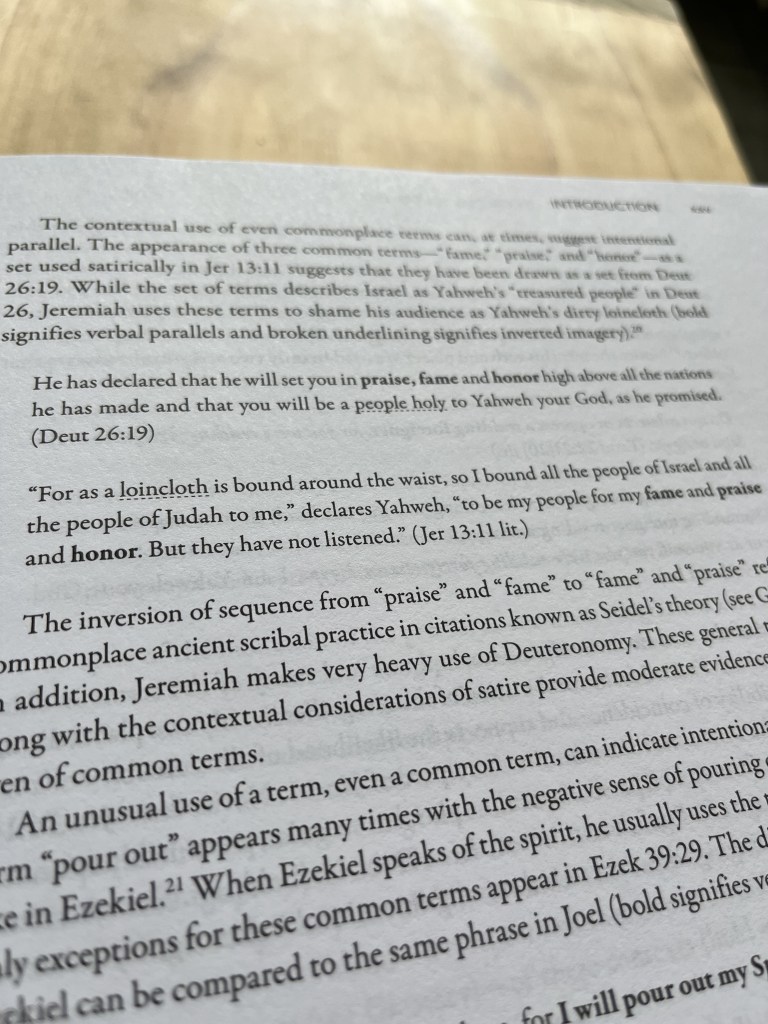

The first two lists include a grading scale. Schnittjer then writes about how Scripture is consistently used in Jeremiah (aka, the hermeneutical profile of the use of Scripture in Jeremiah). Jeremiah’s use of the OT is difficult because of his “constant use of stock phrases, many unique to Jeremiah’s prose discourses and others shared in the poetic and prose discourses” (261). While his poetic and prose discourses share a lot of language with Deuteronomy and the narratives flowing out from it, “the prose discourses practically overflow with shared stock phrases.”

Jeremiah’s “’bold rhetorical, not literal, uses of scriptural traditions reveal a prophet under pressure” (262). Schnittjer then comments on each of Jeremiah’s use of Scripture (from list #1). Some comments are brief (Jer 1:6–9; 2:5), while others are more extensive and include both the donor and receptor texts (2:2; 7:5–6, 9; 17:19–27).

Schnittjer ends with the section Filters, non-exegetical uses of scriptural traditions. These are extensive lists of parallels that you should not skip over as they still help to connect Scripture together.

Certainly anyone could quibble about why a text was or wasn’t used. I checked both Genesis 9:22–23 and Leviticus 18:7–8 and couldn’t find a connection between these texts by Schnittjer.

22 And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father and told his two brothers outside. 23 Then Shem and Japheth took a garment, laid it on both their shoulders, and walked backward and covered the nakedness of their father. Their faces were turned backward, and they did not see their father’s nakedness (Gen 9:22–23).

7 You shall not uncover the nakedness of your father, which is the nakedness of your mother; she is your mother, you shall not uncover her nakedness. 8 You shall not uncover the nakedness of your father’s wife; it is your father’s nakedness (Lev 18:7–8).

Here it seems that when Ham saw the “nakedness of his father,” he actually saw the nakedness of his father’s wife, Ham’s own mother. Given the size of Schnittjer’s book, there are massive amounts of Scriptural connections included, but one shouldn’t expect that every possible connection is made.

Recommended?

This comes highly recommended for students, pastors, and scholars. Schnittjer doesn’t do all the work for you. This is not an exegetical commentary, but Schnittjer’s aim is to help you identify patterns in exegetical contexts. Schnittjer offers accessible insights, while acknowledging that “sometimes scriptural interpretation of Scripture involves extremely subtle, complicated, and difficult issues” (xliv). To know our Old Testament better is extremely vital for our Christian faith. Schnittjer writes, “Studying Scripture backwards and forwards by means of Scripture’s own interpretive interventions offers promise for stronger and more coherent Christian theology,” for “[t]here is no such thing as Messiah or gospel without the Scriptures of Israel” (xlvi). This is an incredible work that will strengthen your knowledge of the OT and , hopefully, by turning to the NT, you will better see how Jesus is the Messiah and how all of God’s promises in him are “Yes.” Highly recommended.

Buy it on Amazon or from Zondervan Academic! .

Other reviews of Schnittjer’s Works

-

- Old Testament Narrative Books (Scripture Connections)

- Torah Story, 2nd ed.

Lagniappe

-

- Author: Gary E. Schnittjer

- Hardcover: 1104 pages

- Publisher: Zondervan Academic (August 17, 2021)

Disclosure: I received this book free from Zondervan. The opinions I have expressed are my own, and I was not required to write a positive review. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255 http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_03/16cfr255_03.html.

Amazon Affiliate Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Wow! What an interesting idea for a book. I will tell my husband about this as he just bought Logos Bible software and has access to many deals on books. Thank you! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Lori! Yes, this a great resource to have on Logos (then it doesn’t take up so much space), and it’s easier to search for Bible texts.

LikeLike

You convinced me

LikeLiked by 1 person

Super!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ordering from Amazon…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great! It’s one I wish I would have gotten when it first came out.

LikeLike