The biblical books are unique in that they are God-breathed, making us wise for salvation in Jesus Christ, with its authors carried along by the Holy Spirit. But why don’t we have the originals manuscripts. Why do we have so many different kinds of manuscripts in Hebrew, Greek, an in other languages? All believers should work at knowing how to read and interpret the Bible. But Michael Shepherd—professor of biblical studies at Cedarville University—believes that an understanding of how the Bible was made can help us be better interpreters of the Bible?

Shepherd emphasizes, “What was produced was exactly what God wanted” (2). Instead of thinking of the Old and New Testaments as “Law vs. Gospel” or “Ancient Judaism vs. the Christian Church,” Shepherd rightly believes we should read the OT as its sees itself: the Law/Torah of Moses and the Prophets and Psalms (or even just “Scripture”), and the NT documents were written either by apostles or those closely associated with them.

According to Shepherd, there is no universally-agreed-upon canon of Scripture. Everyone includes or excludes different books. Shepherd here distinguishes “between books that were shaped in light of one another and books that were produced primarily as exegetical works that assumed a fixed body of scriptural literature” (4). The Old Testament has a three-fold structure: The Law/Torah, the Prophets, and the Writings. The books included in the Writings has the most fluctuation between different sources.

The term TaNaK is an acronym from the three divisions of the Hebrew Bible: Torah, Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings).

-

- Torah: Genesis-Deuteronomy;

- Nevi’im: Joshua-Judges-Samuel-Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Hosea-Malachi;

- Ketuvim: Psalms-Job-Proverbs, Ruth-Song of Songs-Ecclesiastes-Lamentations-Esther, Daniel-Ezra/Nehemiah-Chronicles.

As support for these divisions, Shepherd gives us the canonical seams, the threads that tie these divisions together. The Books of Moses are tied together with the Prophets (Deut 34:5–12 and Josh 1:1–9) which are tied to the Writings (Mal 4:4–6 and Pss 1–2). Shepherd shows how such seams are significant before touching on the NT order.

Chapter 1

How do we read the Bible? The biblical texts are littered with clues: clauses, sections, books, and links between books. The biblical authors guide us in reading their books through the use of words, clauses, sentences, and paragraphs, and they “also read one another and establish[ed] an extensive system of citation” (15). Chapter 1 highlights some of these interpretive clues found in the Bible’s micro- and macro-levels of self-interpretation.

Shepherd shows how the Bible interprets itself as seen in instances of repetitive stories. You know, those stories where something happens, then a character repeats exactly what happened. Yet, as Shepherd writes, “The multiple retellings of a story in chapters like Genesis 24 and 41 are often designed to introduce interpretive elements into the repetition” (20). In each section of Genesis 24 when Abraham sent his servant to find a wife for Isaac, “the providence of God is highlighted in a different way (24:7, 12, 21, 27, 40, 42, 50, 56). This is an important aspect of the author’s worldmaking in which he seeks to depict the real world as one whose events the God of the Bible providentially oversees and orchestrates” (20).

Shepherd offers some brief tips on how to read the different genre in the Bible (narrative, poetry, genealogy, law—treated in ch. 3, and epistle). As we work to interpret those texts, Shepherd suggests we think in terms of probability. Given the evidence, which option is the most plausible? One must weigh the probabilities with other texts and interpretations and make the best choice.

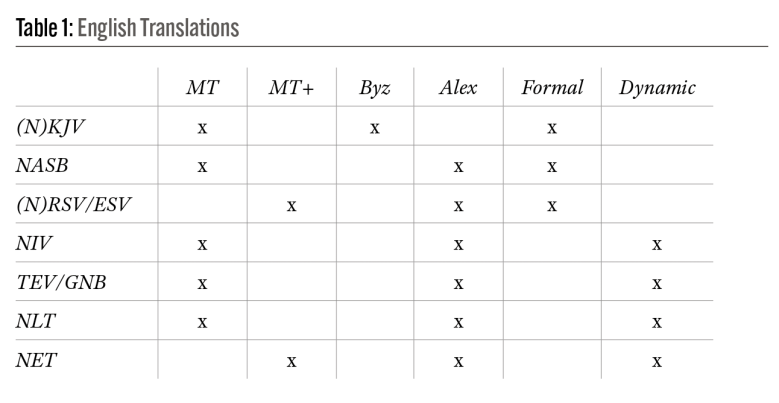

Chapter 2 covers the important work of textual criticism. This occurs when scholars try to ascertain the original “text that stood at the beginning of the transmission process” (45). Shepherd first covers Hebrew texts (the Dead Sea Scrolls) and early translations of the Hebrew Bible (Septuagint/LXX, Syriac Peshitta, Targums, and Latin Vulgate). These early translations are important because “they provide evidence of Hebrew readings in their source texts that differ from other known Hebrew witnesses,” and “they give insight into the different ways in which the Hebrew Bible was received and interpreted at a very early period of time” (49).

Then he covers “variant literary editions,” which is when “an original version of a section or a book is revised to such an extent that it constitutes a new edition. This new edition then has its own process of transmission apart from that of the original edition” (53). He then covers Greek texts of the New Testament: the Alexandrian text, the Byzantine text, and the Western text, where they originated (can you guess?), and how they relate to each other.

He covers English translations, showing which ones used what Greek edition. He explains why we wouldn’t want a truly “literal” translation, as well as the pros and cons of literal vs. dynamic translations. Basically, no translation is “perfect” or “best.” We need to make use of many of them to understand a passage.

Chapters three and four combine the information from chapters one and two to inform how we interpret the Bible. Understanding how the Bible was made meets interpreting what the Bible means. Shepherd combines both an understanding of a biblical book’s literary structure with textual criticism and the interpretive character of translations.

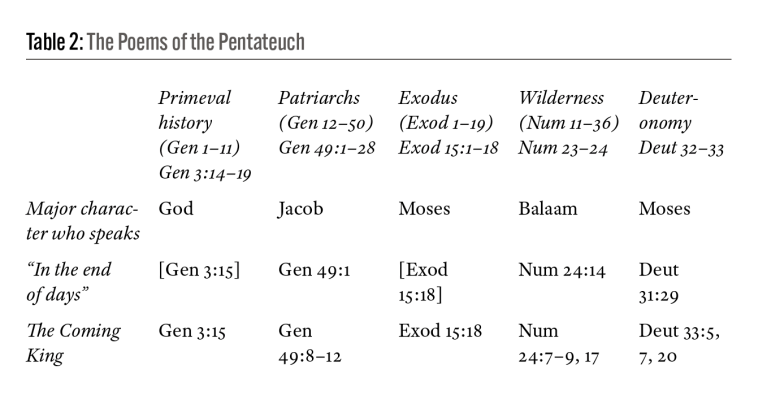

To give one example from this section, within the Pentateuch are large alternating blocks of narrative with poetry, which help interpret the narrative next to it.

Here Shepherd builds upon John Sailhamer’s work. He views these poems as interpreting the preceding narratives in order to highlight the theological message of the Pentateuch. As Shepherd observes, “Each poem features a major character from the preceding narrative as the speaker, an expectation of what will happen in the last days, and a prophecy of a coming messianic figure. Thus, the author does not see the storyline of his book as a mere documentary of past events but as an opportunity to speak of the future work of God” (71).

Here’s where we see the meaning and the making of the Bible come together. In Balaam’s third oracle (Num 24:3-9) he speaks of a king who will be higher than “Agag” and whose kingdom will be exalted (24:7b). Shepherd believes the Masoretic Text’s reading of “Agag” is “most likely a historicized version of the prophecy that refers to the defeat of the Amalekite king (Agag) by Israel’s first king (Saul) in the story of 1 Samuel 15” (77). However, the Samaritan Pentateuch and the Septuagint have “Gog” instead, referring “to an eschatological enemy to be defeated by the messianic king (Ezek 38-39; Rev 20:8)” (77).

In Balaam’s final oracle (24:15-24) advises Balak, king of Moab, about what Israel will do to his people (Moab) “in the end of days” (Num 24:14)—the same phrase that appears in Genesis 49:1 and Deuteronomy 31:29. According to Shepherd, “Balaam is explicit that his last oracle looks beyond the history of Israel to the last days” (78). In Numbers 24:17a, Balaam says that he sees “him” but not now, “him” but not near. This is “the coming king mentioned in Numbers 24:7-9” (78).

But how will this king come?

- The Masoretic Text for Numbers 24:17b says, “A star treads from Jacob, and a scepter rises from Israel.”

- But the Septuagint translates this verse instead, “A star will rise [anatelei] from Jacob, and a man [anthropos] will rise up from Israel” (cf. LXX Num 24:7a: “a man will go forth from his seed”).

- This translation connects this text to numerous other messianic prophecies in the Septuagint where a coming one is known either as

- the “rising one” (anatole)

- see LXX Jer 23:5; Zech 3:8; 6:12; cf. Luke 1:78

- as a “man” (anthropos)

- see LXX Isa 19:20; cf. 2 Sam 23:1; Zech 6:12; Dan 7:13; John 19:5; 1 Tim 2:5; see also Mal 3:20; Matt 2:2; 2 Pet 1:19; Rev 22:16.

- the “rising one” (anatole)

- This translation connects this text to numerous other messianic prophecies in the Septuagint where a coming one is known either as

Shepherd summarizes all of the poems and observes that this macrostructural arrangement informs how we read the lower levels of the texts. This also cues us into what Jesus meant when he said that Moses wrote of him (John 5:39, 46–47; 8:56).

In this chapter Shepherd also looks at the role of the law within the Pentateuch. It is fascinating his note that the Pentateuch and Prophets were new covenant documents because they saw the end of the Mosaic covenant coming and that a new covenant would then be given in the future (Deut 29) to open eyes and hearts. Shepherd surveys various laws to give you an aim of how to think about them as a new covenant Christian. He surveys more links within the Old Testament making this an incredible chapter that will help piece together the OT like you (likely) haven’t heard before.

Chapter four covers the New Testament writings. I wrote plenty on chapter three, so I won’t belabor the point here. But Shepherd’s work on the compositional strategy of the New Testament is illuminating.

The fifth chapter looks at the Bible holistically via the extensive system of intertextuality among the books. This final chapter invites readers to enter the textual world of the Bible by faith, allowing it to define, explain, and represent reality. Shepherd removes the curtain and shows a world of complex intertextual relationships between the biblical books. This literary world “defines and explains the real world. It is the biblical authors’ theological representation of reality” (147). He looks at the web-slinging that occurs with two themes: the kingdom of God and the covenants. There is plenty of detail here that helps bolster Shepherds final point that churches and pastors should actually teach the Bible to their congregants. Church members need to know how to read and understand the Bible to be shaped (or recontextualized) to the Bible and its story. The Bible shows us Christ, and we need to be formed into him and his likeness. That is accomplished as we are shaped “by the study of Scripture itself” (170).

The Spoiled Milks

So much of this book was good, and I’m going to have to work through it again with an open Bible to catch all the seams and connections. But my only complaint is that the making of the Bible doesn’t play as big of a role as what Shepherd let on. While noting some differences between the LXX and the MT concerning specific texts, as well as the seams put together by later editors (such as his comment about the first few chapters of Judges), the making of the Bible doesn’t play a huge role in how I understand the Bible, according to this book. It does play a role, more than what other books let on, but nothing paradigm-shifting.

Recommended?

Shepherd has given us an incredible work of detail and insight into the shape of the Bible. God wants us to know his word without becoming eggheads. We ought to learn the Bible not merely to gain information like its currency, but so we might understand our good God and the salvation he has wrought for us in his Son. While many laypeople will likely either skim or skip chapter two, Shepherd’s book will give them a greater appreciation for how the Bible is put together and how skilled and insightful the biblical authors were. These guys were brilliant, and we don’t often quite understand just how brilliant they were.

Buy it on Amazon or from Eerdmans!

Lagniappe

- Author: Michael B. Shepherd

- Paperback: 259 pages

- Publisher: Eerdmans (April 2, 2024)

Review Disclosure: I received this book free from Eerdmans. The opinions I have expressed are my own, and I was not required to write a positive review. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255 http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_03/16cfr255_03.html.

Amazon Affiliate Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.