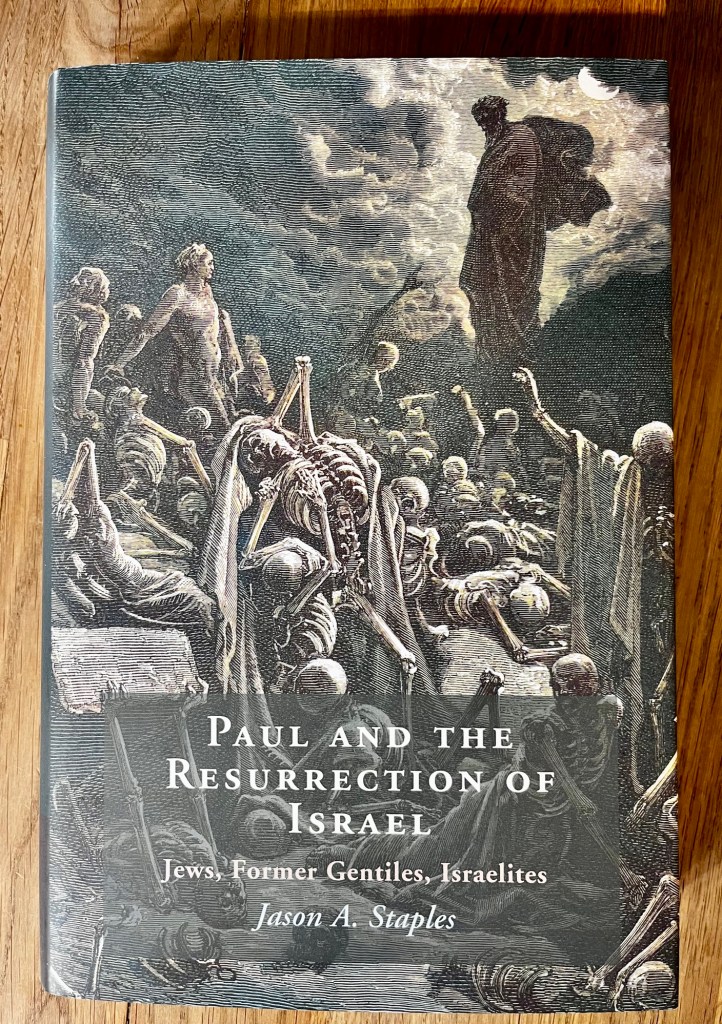

This is the book. What is the mystery of Romans 9–11? Why are these chapters so difficult to understand, yet why are they so critical? Was Paul merely inconsistent in his argument? The gospel has gone to gentiles, no wait the Jews are still important? Staples argues against all of these and says that Paul was not inconsistent, confused, or just writing off the cuff and using OT texts ad hoc (see the more technical term “willy-nilly”). Instead, Paul was right at home in the world of Second Temple Judaism and held the same sort of Jewish restorationist eschatology that other Jews held, and that this would be fulfilled in Jesus Christ.

Jason Staples—assistant teaching professor in the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at North Carolina State University—places himself within the broad movement called “Paul within Judaism,” while also being critical of it too.

Staples cites prophetic promises from the OT that God would restore the northern kingdom of Israel from the nations. For example, in Romans 9:22–26, Paul quotes from Hosea when he writes,

22 What if God, although choosing to show his wrath and make his power known, bore with great patience the objects of his wrath—prepared for destruction? 23 What if he did this to make the riches of his glory known to the objects of his mercy, whom he prepared in advance for glory— 24 even us, whom he also called, not only from the Jews but also from the Gentiles? 25 As he says in Hosea:

“I will call them ‘my people’ who are not my people;

and I will call her ‘my loved one’ who is not my loved one,” [Hos 2:23]26 and,

“In the very place where it was said to them,

‘You are not my people,’

there they will be called ‘children of the living God.’” [Hos 1:10]

This is fulfilled when gentiles (who are “not God’s people”) follow Jesus Christ as Lord. They receive the Spirit, become Abraham’s seed and thus part of Israel, experiencing the redemption originally promised to them.

“Jew” and “Israel”

Many believe that Paul wrote about Jews and Israel interchangeably. Whichever word he used didn’t really matter much; they both meant the same thing. One thing that Staples argues for is that the Jews were a subset of the larger superset “Israel.” The idea runs like this:

In the book of 1 Kings, Israel split into two kingdoms, Israel and Judah. Israel was dispersed by the Assyrians, and Judah was exiled to Babylon. When Judah returned (Ezra 1:5), the people were called Jews (Jew is derived from the Hebrew term Yehudi (lit. “of Judah”), which passed into Greek as Ioudaios). We see in Ezra that the priests, Levites, and the rest of the exile celebrated the dedication of the house of God with joy by offering sacrifices. Among these was a sin offering for all Israel, twelve male goats, one for each of the tribes of Israel (Ezra 6:17).

Although most of the tribes were missing (having been dispersed by Assyria), sin offerings were still offered for them because the remaining tribes believed God’s promises about their future restoration.

How is “Israel” Significant?

Paul rarely uses the term “Israel” in his letters, but he uses it thirteen times in Romans 9–11. He refers to “Jews” only twice in these three chapters, but numerous times in his other letters. Why is this? Staples points to Second Temple Literature (STL) and says that “Israel” referred to:

- the people of the biblical past;

- in cultic settings (so referring to the “God the Israel” in prayers); and

- “referring to eschatological Israel, including both Jews and northern Israelites” (58).

Because Israel rebelled against God’s torah, they experienced the covenantal curses, specifically exile (also called “death,” Ezek 37; Deut 30:17–20). God would “redeem, reunify, and restore all twelve tribes of Israel to covenantal favor,” and this would include the inward transformation of the heart as promised through the new covenant. Staples’s line of reasoning explains how Jeremiah can give the promise of the new covenant to “the house of Israel and the house of Judah” (Jer 31:31) and yet gentiles are included in Hebrews 8:8–12.

Before Jesus ascended to the Father, the disciples asked Jesus, “Is this the time that you restore the kingdom to Israel?” (Acts 1:6). If Jesus the Messiah came to restore Israel through his death, why hadn’t it happened? Yet what happens next? The Spirit is given as promised (Acts 2:33, 38) in connection with the new covenant (Ezek 36:26–27; Jer 31:33) so that those who receive the Spirit are God’s people. So when Gentiles begin to receive the Spirit in Acts 10:44–45, they become sons of Abraham (Gal 3:7, 14). Paul was controversial among other Jews because he insisted that “the eschatological hopes of Israel were already being fulfilled through Jesus,” as well as that uncircumcised non-Jews “could be included as full members of the new covenant” (106).

The Rest—Romans 1, 2, 9–11

This leads us to the book of Romans, which Staples believes is “a defense of how gentile incorporation in the ekklesia following Israel’s messiah is inextricably linked to Israel’s salvation and is paradoxical proof of God’s faithfulness to Israel” (111). For the rest of the book (chs. 3–7), Staples both surveys and dives deep into Paul’s argument in Romans.

Chapter 3—the Israel Problem and the Gentiles

Chapter 3 covers Romans 1 and how all people, “Israel foremost of all,” are sinners and are subject to God’s wrath (135). Just being a Jew who knows Torah is not enough to escape God’s wrath. But those who, as Staples translates, “both hear and obey, ‘persevering in good works’ will receive ‘glory, honor, and immortality’” (Rom 2:7).

In fact, as Staples writes, “possession of the Torah, birth, and circumcision provide no security against God’s impartial judgment if one does not behave justly” (142). So a “disobedient Jew will receive the same punishment as a sinful gentile,” but then at the same time a gentile who doesn’t have the torah who “does the things of the Torah” (Rom 2:14; cf. Deut 6:4; Heb 3:16, 18–19) will receive the same “glory, honor, and immortality” (142).

Chapter 4—Salvation Through Justification

In chapter 4, Staples reads Romans 2 in light of the new covenant promises of Israel’s heart transformation and the inclusion of gentiles. The Torah revealed Israel’s stubborn hearts, but it could not repair it. God had promised to circumcise Israel’s hearts (Deut 30:6), writing it on their hearts (Jer 31:33), giving them a new heart and spirit (Ezek 36:26), which would finally enable them to “keep the command and ‘love YHWH your God with all your heart and all your soul, so that you may live’ (Deut 30:6)” (146). In this way, God is going to change people. “Rather than unjustly judging the unjust to be just, God will transform the just into ‘doers of Torah’ who can then by justly judged ‘just before God’ (2:13)” (146).

According to Staples, the reason the gentiles should be included as full participants into the new covenant is because they “do the things of the Torah” (Rom 2:14) due to the outpouring of the Spirit. Instead of receiving “free grace” where Christians should try to live good lives but if we sin a whole lot instead “oh well, that’s okay, we’re forgiven anyway,” the term “grace” in Greek implied “reciprocal gift-giving” (175). God’s grace works in relationship and brings about obedience. God expects these things. This is in accord with what is promised in Deut 30:6, that Yahweh would circumcise Israel’s hearts in order to love him with all their heart and soul. The gospel isn’t “Torah-free”; it is “Torah-implanted.” On the last two pages, Staples shows the line of thinking in Romans 3–8 to get us up to speed with Romans 9–11.

Chapters 5–7—God’s Fidelity, God’s Justice, and Israel’s Mysterious Salvation

Chapters 5–7 cover Romans 9–11 and how uncircumcised gentiles who receive the Holy Spirit does not undermine God’s promises to Israel but represents God’s faithfulness and power to Israel. These chapters explain

- how the uncircumcised were being incorporated and;

- why the reunification and restoration of all twelve tribes of Israel seems not to be happening as anticipated (186–87).

God has been “over-faithful,” even extending redemption to gentiles to fulfill his word and redeem “all Israel” (11:26). A few things Staples looks at would be:

- the imagery of the Potter and the clay and the meaning of “vessels of wrath”;

- how to understand Jesus as the Just one spoken of (perhaps, prophesied?) in Habakkuk 2:4;

- As Staples writes, “Israel’s justification depends on the spirit, and the spirit comes from Israel’s faithful messiah, not from ‘works of Torah’” (264). So since Jesus fulfilled Leviticus 18:5b (Gal 3:11), he can justify Israel through pouring out his Spirit onto them, and he can extend the blessing of Abraham to the nations.

- how to understand Romans 10:6–8;

- how to understand the pruning of the olive tree and grafting in the wild olive branches; and

- Paul’s mystery, “the fullness of the nations,” and how that connects with Gen 48:19 and Ephraim (also the epithet for the Northern Kingdom).

Chapter 8—The End

The final chapter (ch 8) offers a true conclusion—the strength of Staples’s reading with connections to the cosmic dimensions. One payoff is that Staples’s argument makes a lot of sense. God will keep his promise that “all Israel” will be saved, and if Staples’s argument is correct, gentiles who follow Jesus are part of “all Israel.” I believe—and I hope I’m right—that many scholars of different stripes (OPP, *Reformed, NPP, etc.) will agree with large portions of Staples’s argument. Yes, there will be things they quibble with or largely reject (many in the Reformed community will probably disagree with Staples’s argument of the Potter/clay imagery), but much of this is really excellent and solves a lot of the controversial texts in Paul.

*Many of Staples’s arguments still work within Reformed theology (such as salvation being conditioned upon our works; God circumcising our hearts in order to love him).

Recommended?

Matthew Bates wrote that this book is the most important book on Paul since John Barclay’s book in 2015. What I can tell you is that so much of this book made sense. I still have questions about the implications of Staples’s interpretations. And this requires both a greater knowledge of PwJ interpretations as well as Staples’s own critiques. But what I’ve heard so far from him makes a lot of sense and is worth thinking through.

Staples does a lot of heavy lifting in his book. It is required for his task, but it is oh so worth it. I’ve never heard of Jewish restoration eschatology before this book, but now I want to look more into it. I’ve been wanting to read the Apocrypha and other Second Temple Literature, and if Staples is correct, understanding these neglected books is important in understanding Paul as a first-century Jew who believed Jesus as the Messiah who fulfilled the OT. This is absolutely my favorite book this year, but also my favorite book that I’ve read for a long time. Staples provides greater coherence to Paul’s theology and answers numerous questions. Highly recommended!

Buy it from Amazon or Cambridge University Press!

Related Post:

Lagniappe

- Author: Jason A. Staples

- Hardcover: 435 pages

- Publisher: Cambridge University Press (January 11, 2024)

- Read the Preface, Intro, and Table of contents

- Onscript podcast

Buy it from Amazon or Cambridge University Press!

Review Disclosure: I received this book free from Cambridge University Press. The opinions I have expressed are my own, and I was not required to write a positive review. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255 http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_03/16cfr255_03.html.

Amazon Affiliate Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Welcome to my world. Believe it or not, over 40 years ago, I was taught many of these ideas as an adolescent by an uncle with biblical/historical insight. It changes who you are and how you view the world. Dr Staples has given a great gift to the household of faith with his two books. Joseph, is alive among the nations!

LikeLiked by 1 person