The Center of Paul

Is there a center in Paul’s theology?

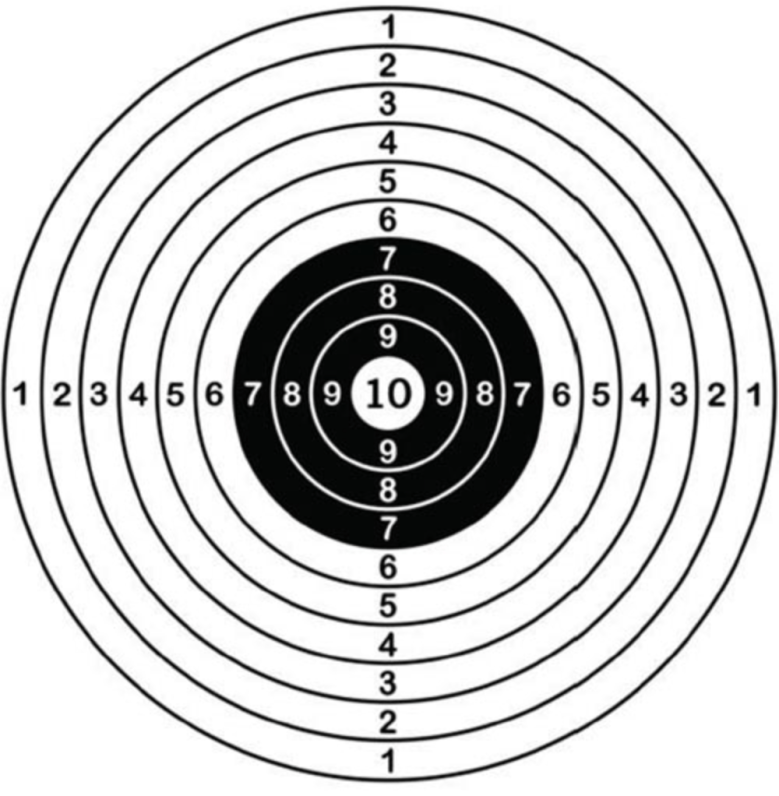

Schreiner writes that the problem with this approach is that we can too often make a mental picture of a bullseye, with themes circling the supposed center. Those themes that are nearer to the center are more important, and those floating further away are seen as not as important. Some have argued for justification, reconciliation, being “in Christ,” participating in Christ, salvation history, or the imminent apocalyptic triumph of God as being Paul’s centerpiece of his theology. According to Schreiner, “Each theme fails as the ‘center’ for the same reason. Every proposed center suppresses part of the Pauline gospel. Identifying the center as, say, justification exalts the gift given above the giver. The gift of righteousness is not more important in Paul’s thinking than the person who gave the gift.” (4)

Instead, Schreiner, through an inductive study of Paul’s thirteen letters, aims to show that God in Christ is central to Paul, and that everything emanates from that. Romans 11:36 states that all things come “from Him,” that is, from God. “God is the source of all things—he is the foundation” (p. 6; see 1 Cor 8:6 and how “we exist for him”). All of the gifts believers receive come from God, the giver. He is the foundation. As Schreiner writes, “The ultimate reason for the creation of the world and for the fulfillment of salvation history (see Rom 11:36) is for the sake of the Father and the Son” (9). “God is the center of Pauline theology,” but that does not diminish Christ’s centrality. Schreiner again, “The exaltation of Jesus the Messiah brings glory and praise to God. Perhaps we can say that God in Christ is the foundation of Pauline theology” (9). In fact, it was magnifying God in Christ that was Paul’s “animating principle” (26).

Paul. Redux.

Who was Paul?

Paul was an apostle sent out to convert and teach believers about what God has done in and through Christ and thus how they should live as new creations. Paul wasn’t an ivory tower theologian whose sole purpose was to write theological treatises. He was a giant of a theologian, and “he was a missionary who wrote letters to churches to sustain his converts in their newfound faith. He saw himself as a missionary commissioned by God to extend the saving message of the gospel to all nations. Thus he was fulfilling the covenant promise given to Abraham that all nations would be blessed through Israel” (27). Paul was an apostle, a missionary, a pastor who cared for his churches, and as one continuing in the role of Isaiah’s servant (Acts 13:47; Is 49:6). His ultimate goal of missions was to see God glorified among both Jews and Gentles together.

Paul was a missionary because he believed that God’s promises to Abraham of blessing the world had been fulfilled in Christ. Because of Christ’s work, Jews and Gentiles would experience a second exodus, this time out of sin, a new covenant under which they would experience forgiveness of sins and be able to keep God’s law now written on their new re-created hearts, led by a new David King, the eternal Messiah, and would be new creations with the down-payment of God’s Holy Spirit. This is all done through the cross-work of Christ. All believers are made righting God’s sight through their faith in Christ and his cross-work (the death and resurrection) for them.

Righteousness

While Schreiner does focus primarily on Paul’s writings, he does bring in other scholars and their arguments either to bolster his own or to show how their arguments fail to make sense of the evidence. In regards to righteousness, some complain that righteousness is only a mere “legal fiction” if it is forensic. However, Believers truly are in a right relationship with God because of Christ’s work. And because we are in such a right standing, we are able to be united with Christ, receive God’s Spirit, and walk in his power to live new lives that please him.

Others like Käsemann, Stuhlmacher, Martyn, de Boer, Campbell, and Gaventa argue for an apocalyptic reading of God’s righteousness where “righteousness is not merely individualistic but also includes all of creation. God’s righteousness is manifested when he restores the world to his lordship in the saving work of Christ” (209). Or, according to Käsemann, God’s righteousness is not only forensic, but transformative. He both declares and makes righteous those who are saved.

Or perhaps it refers to God’s covenant faithfulness, a la N.T. Wright. Schreiner gives some space to explain Wright’s view, intermixing it with his explanation of his own view. Schreiner has written on this topic elsewhere, which he refers to in his footnotes. (I wrote on it as well when I reviewed Schreiner’s revised Romans commentary.)

That said, Schreiner gives a defense of his own view of what Paul means when he refers to “the righteousness of God.” He writes,

Righteousness does not merely denote “justice” but God’s intervention on behalf of his people (211).

We can read this in Psalm 98:2–3 and Isaiah 51:5–8 (cf. Ps 31:1; 36:10: 40:10; 71:2; 88:10–12; 143:1; Is 46:13). Schreiner again notes, “God’s righteousness expresses his faithfulness to his covenant, and yet this is not the same thing as saying that God’s righteousness is his faithfulness to the covenant. God’s righteousness fulfills his covenant promises, but it does not follow from this that we should define righteousness as covenant faithfulness!” (212). As well, that we “become the righteousness of God” through Christ’s atoning death in 2 Corinthians 5:21 can hardly mean that we become God’s “covenant faithfulness.” Yet “it fits to understand it in terms of God’s saving work through Christ by which he declares the believer to be in the right before him” (214).

The Law and Christ’s Law

Schreiner shows how the commands from the OT law like dietary restrictions, keeping the Sabbath, and circumcision, are no longer in effect under the new covenant. Yet Paul also refers to other OT commands as ones that are biding on believers and so ought to be adhered to: “prohibitions against idolatry, murder, adultery, stealing, and lying, as well as the command to honor one’s parents” (359).

The Mosaic covenant is no longer in force because it has been fulfilled in Christ. All the commands of the law point to something, or rather, Someone. but that this covenant is fulfilled in Christ. Thus all the commands of the law, including circumcision, point to something, even if we don’t literally practice them now. For example, circumcision anticipated the circumcision of the heart. Old Testament sacrifices anticipated the final sacrifice of Christ (Rom 3:24-26). However, as Schreiner notes, “The prohibition against adultery passes over into the new era intact, without any change in content, though Paul emphasizes that the Spirit provides the strength to obey the command. Believers now fulfill the law of Christ (Gal 6:2; 1 Cor 9:21) in the new-covenant era. The laws that are still required aren’t required because they are part of the Mosaic law; they are required because they are part of Christ’s law” (359).

Paul writes that children should obey their parents as they will receive the promise of living long on the earth. In the Old Testament this promise related to a long life in the Promise land that God gave Israel. But the church has land it can call its own. In keeping with Paul’s theology, the inheritance promised to Abraham has been extended to the world in Christ (Rom 4:13). The inheritance refers to the future glory awaiting believers (Rom 8.17)! It relates to our heavenly inheritance. Schreiner writes, “In other words, those who obey their parents will receive an eschatological reward—the inheritance promised to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. They will not receive that reward in this life but the next. We have here not an earning of salvation but the evidence of God’s saving work” (360).

Those who completely eliminate any obedience to the law in the new covenant fail to understand Paul.

“Keeping the law by the power of the Spirit is not legalism, nor does it quench freedom. On the contrary, it is the highest expression of freedom (2 Cor 3:17).”

Pick up 40 Questions about Christians and Biblical Law by Schreiner for more.

Recommended?

Schreiner covers other topics such as how suffering was the means for spreading the gospel (ch. 4), the violation of God’s law and the power of sin (chs. 5 and 6) as the means of dishonoring God, the person and work of Jesus Christ (ch. 7), God’s liberating work in believers through his divine grace (sanctification, reconciliation, salvation, redemption, triumph over evil powers, propitiation, election; ch. 8), the Holy Spirit work in us to live a new life (ch. 9), faith and hope through persevering (ch 11). Church life is covered in chapters 13 and 14 (spiritual gifts and ordinances) and how we live in the world (ch. 15). There is much more that could be said (it’s true; Schreiner wrote 576 pages of it), and I won’t try to cover more here.

Who is this book for?

On the one hand, this is for college and seminary level students, as well as scholars and pastors. Casual readers might find themselves in the deep end, but laypeople with a good handle on the Bible generally and Paul specifically may want to try their hand at this book. Schreiner is Calvinistic/Reformed, Baptistic, and stands in the progressive covenantalist camp (although that aspect doesn’t make a huge impact here, at least not explicitly). He is a clear writer with a good grasp of Paul’s theology and connections. He argues for his points cogently, and he presents others’ arguments faithfully. You will come to know and be blown away by Paul’s writings, and hopefully—I make no promises—you will find yourself more in awe of Christ too.

Highly recommended.

Lagniappe

- Author: Thomas R. Schreiner

- Paperback: 576 pages

- Publisher: IVP Academic; revised edition (January 7, 2020)

Buy it from Amazon or IVP Academic!

Disclosure: I received this book free from IVP Academic. The opinions I have expressed are my own, and I was not required to write a positive review. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255 http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_03/16cfr255_03.html.

Amazon Affiliate Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.