I really like the ZECOT series. I’ve reviewed most of the volumes so far, and I have enjoyed all of them. All that I have reviewed have dealt with the Minor Prophets. Aside from Hosea’s 14 chapters, these are books with only a few chapters. In this new commentary on Leviticus, Jay Sklar tackles the structure of the 26-chapter Leviticus and adapts it to this style commentary.

If you’ve read any of my reviews, you’ll know that the aim of this series is discourse analysis (also called macrosyntax). Discourse analysis is a tool used to understand the flow of thought. How words are built into clauses, clauses into sentences, and sentences into paragraphs which serve “as the basic unit of thought” (x). Ultimately it seeks then to understand how those paragraph ideas relate to one another within a whole book. Daniel Block, the general editor, writes that “too little attention has been paid to the biblical authors as rhetoricians, to their larger rhetorical and theological agendas, and especially to the means by which they tried to achieve their goals” (ix).

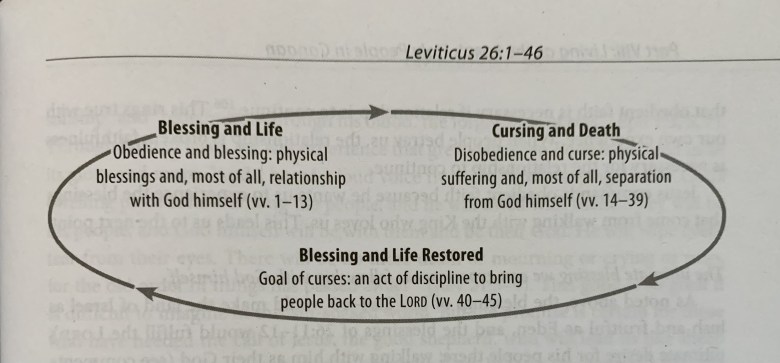

Building off of his Leviticus volume in the TOTC series, Sklar offers a 65 page introduction to Leviticus. He considers the geographical setting of the Israelites and how they had come out of Egypt, had traveled to Sinai and camped there for a total of 11 months and 19 days, and then how they afterwards travel to Kadesh and remained in the plains of Moab for a total of 40 years. What Leviticus does is it takes the Israelites on a journey, “a return to God’s purposes in creation” (3). Just as in Genesis, the Lord separates, blesses, and calls a people to himself. He will give them rest (Gen 2:3; Lev 23:3; 25:1–7), walk with them (Gen 3:8; Lev 26:11–12), and shine his favor on them so that they will be fruitful (Gen 1:28; Lev 26:9).

However, unlike the opening chapters of Genesis, Leviticus takes place in a world corrupted by sin. Atonement then plays a large factor in this book. Sklar writes,

“[Leviticus] casts a vision that takes the Israelites back to the Lord’s intent for humanity from the beginning of the world: to walk in rich fellowship with their covenant King, enjoying his care and blessing, and extending throughout all the earth his kingdom of justice, mercy, kindness, righteousness, holiness, and love” (4).

Authorship and Date

Sklar interprets Leviticus according to the final form of the text. He takes most of Leviticus to have been written in the second millennium BC. He gives a few examples showing how portions of Leviticus fit a dating from that period, which, while not proving that the whole book comes from that period or from Moses, it at least offers the possibility that other portions of the text (other than the examples given) can come from that period as well. The Pentateuch suggests that Moses was the author.

Theology

Leviticus teaches us that the Lord is the Israelites’ covenant King who dwells with them. He is the holy who redeems a sinful people and gives them his holy law. The Israelites would not have been viewed as oppressed if they had followed God’s law but praiseworthy.

In regards to sin and impurity, Sklar offers various tables illustrating the levels of difference between the ritual stages (pp22–23). Sklar asks the question, “Would others look down on those who were ritually impure?” (27). The likeliest answer would be “no”! Most cases of ritual impurity resulted from natural processes or activities like sex, menstruation, childbirth, and mourning. Ritual impurity was a common part of life, and might be similar to how we view people with a cold. Some of us might keep our distance, while others hang around the contagious perosn while remaining cautious.

Atonement

There has been not a little discussion over the meaning of the Hebrew word כִּפֻּר (kippur, “atonement”). Does this atonement ransom the sinner or the impure or does it purify them? Sklar argues that kippur can mean either one depending on the context. The reason for this is because the kippur sacrifice is used in contexts of both sin and impurity. As Sklar writes, sin endangers and pollutes while impurity pollutes and endangers. Unintentional sin endangers the sinner’s life, and the sacrificial blood of an animal ransoms the sinner’s life. Likewise, Israelites are said to be “cleansed” on the Day of Atonement (16:30), and sin defiled the sanctuary (16:16). Sin both endangers and pollutes.

Impurity on the other hand pollutes and endangers. For instance, major impurity defiles “the sanctuary and its contents, even if [such people] have not had direct contact with them” (31). So the Most Holy Place becomes defiled even though almost no one is allowed in there (Lev 16:16). As well, those who suffer from a major impurity must bring a purification offering (Lev 12:6; 14:19). Sklar writes, “Since the blood of this offering has a purifying function (Lev 8:15) and is placed on the sanctuary and its contents, it follows that the sanctuary and its contents have been polluted by the major impurity and must be cleansed” (31). How does impurity endanger? Even when this is done unintentionally, it is a major sin to defile the holy objects in the sanctuary (see Num 6:9–12). In this instance, “the kippur-rite must cleanse the impurity (purification) and rescue the endangered person (ransom)” (31).

Sklar also surveys the subject of legal penalties, their seriousness, how they compare with other ANE laws, and if the penalties were even required. He surveys sacrifice and animal rights, ritual, and Leviticus and the New Testament. He takes a moment to look at some of the distinctive literary features of the book as well as explain his distinctive approach to discourse analysis and how it is represented in this volume.

Outline of Leviticus

Often times how someone says something is just as important as what they say. Sklar divides Leviticus into eight parts (not all of the titles below are Sklar’s; I’m mostly trying to summarize the ideas):

- 1–7: Properly Worship through Offerings

- 8–10: The Start of Public Worship of the Lord at His Palace

- 11–15: Covenant Laws on Ritual Impurity

- 16: The Day of Atonement

- 17: Laws on Slaughtering and Eating Animals and Using their Blood

- 18–20: Covenant Laws on Holy Living

- 21–24: Laws Regarding the Lord’s Holy Things and Holy Times

- 25–27: Living as the Lord’s Holy People

Leviticus 10—Strange Fire; No Mourning.

Sklar divides Leviticus 10 into two halves, the first focusing on priestly unfaithfulness and the second on priestly faithfulness. There also seems to be a sort of chiasm, The two instructions for priests (vv 6–11, 12–15) are surrounded by the disobedience and deaths of Nadab and Abihu (vv 1–5) and the obedience of Aaron (vv 16–20).

1. A tragic example of priestly faithlessness (10:1–11)

A Disobedience and deaths of Nadab and Abihu (vv 1–5)

B Instructions for priests (vv 6–11)

2 A godly example of priestly faithfulness (10:12–20)

B Instructions for priests (vv 12–15)

A’ The obedience of Aaron (vv 16–20).

Since the original Hebrew had no chapter divisions, chapters 9 and 10 would have been read together, one after the other. The events of chapter 10 occurred on the same day as those of chapter 9. In keeping with the series’ focus on discourse analysis, Sklar writes that readers owuld have closely joined these two chapters, “especially since the verbal form that begins 10:1 carries on the story of 9:24. And while this verbal form allows for several hours to have passed between 9:24 and 10:1, the smooth transition gives the impression that the Israelites are still shouting for joy in the background as Nadab and Abihu begin their fatal deed” (293).

According to Sklar, what is implied in Leviticus 10:1 is that Nadab and Abihu were trying to barge into the Most Holy Place—the King’s personal throne room— according to their own prerogative, showing utter disregard for the King (10:3). (Think of Esther 4:11.) Leviticus 16:1 seems to refer back to this event when the Lord warns Aaron not to enter the Most Holy Place whenever he pleases. The brothers’ fire would have consisted of live coals (Num 17:2) and incense (Exod 30:34–36), but they offered it at the wrong time (that of their own choosing) and in the wrong place (in the the Lord’s own throne room). The command against priests drinking wine or strong drink in 10:9 may imply that Nadab and Abihu were somewhat inebriated when they sinned.

When Moses tells Aaron not to mourn, this has to do with mourning rites, not emotions. Aaron and his remaining sons could still grieve their loss, but they could not engage in specific mourning rites that would make them ritually impure.

Leviticus 11—Clean and Unclean Edibles.

The taxonomy of clean and unclean animals may very well have already been held by the Israelites, at least to some degree. It seems the Lord used existing Israelite concepts about animals and “codified them as covenantal to set the Israelites apart from the nations and to teach them aspects of living as his holy people” (322). As they understood how their ritual impurity defiled the Lord’s sanctuary, they would continually learn that their moral actions can defile and be sinful as well.

But why are some animals pure or impure? Scholars have tried to figure out an overarching explanation behind why an animal is considered pure or impure. After listing four different explanations, Sklar argues that there is no single explanation that accounts for all the data. As well, “it is difficult to explain why the text would sometimes identify physical characteristics as guidelines and sometimes not” (323). Just thinking about how cultural norms works, we usually don’t have an explanation for why we do certain things and not others. Most if not every “Israelite might not always have been able to identify a rationale for why a certain animal was impure” (323). If someone from a country that considers dog meat a delicacy were to ask a Westerner why we eat cow meat but not dog meant, that Westerner (myself included0 wouldn’t really know what to say. That just is the way it is. If we asked an ancient Israelite, “Why does a land animal have to chew the cud to be pure?” he might respond, “I don’t know. I’ve never thought about it; that’s just the way it is” (323).

Leviticus 19—Mixtures and Fruit Trees.

Laws about mixtures (19:19).

Why can’t two different kids of animals mate, two different kinds of seed be sown, and a garment be made of two or more kinds of material? Sklar agrees with Milgrom’s “very plausible” approach “that mixtures belong to the sacred sphere, namely, the sanctuary,” and because of that the Israelites were forbidden from them (Sklar-535, Milgrom-1660).

- First, in the ANE heavenly beings were often mixed creatures (think of Ezekiel’s angels in Ezek 1:5–11).

- Second, if an Israelite sowed a second seed in his vineyard and produced a mixed crop, all the produce wuold be considered “holy” and it would have to be given to the tabernacle (Deut 22:9).

- Third, there were som priestly garments (Exod 28:6; 39:29) and tabernacle curtains (Exod 26:1) that were made of mixed fabrics due to their ritually holy status.

Laws about fruit-tree crops (19:23–25).

This is one of those odd laws that doesn’t make sense and appears at first (or tenth) glance to have no theological relevance. The food trees in view would have been ones that bore olives (Exod 23:11), dates (Exod 15:27), figs (Deut 8:8), or pomegranates (Deut 8:8). For three years this fruit would be “forbidden.” In the fourth year the fruit is suddenly considered “holy” and would be treated as a firstfruit given to the Lord. In the fifth year the Israelite could eat the fruit.

What significance is there here? First, an Israelite would have “an opportunity to honor the Lord as their gracious provider” and as their holy God (538). But there are also allusions to the garden of Eden. The Lord “planted” a garden in Eden where “every tree” was good for “food” (Gen 2:8–9). In Canaan, the Israelites would be doing the same thing, “planting” various trees (lit. “any tree”) good for “food” (Lev 19;23). Canaan is thus reimagined as a second Eden. Just as Adam and Eve were forbidden from eating some fruit, yet failed, “so the Israelites are forbidden from dong the same here… and in this way are given an opportunity to show their love and obedience to the Lord in ways Adam and Eve failed to do” (538). Sklar adds, “We honor the Lord as holy by walking obediently in his holy commands” (538).

Commentary Structure

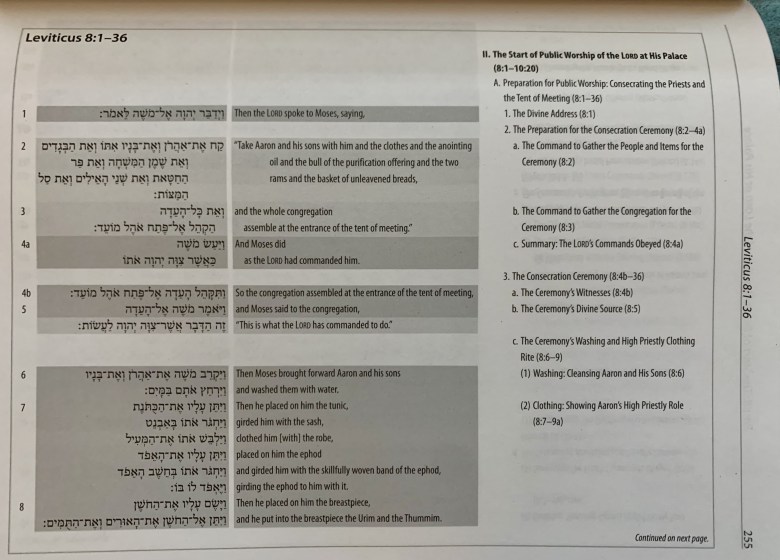

Each chapter follows the same structural path:

- Main Idea of the Passage. The main points are condensed into 1-2 sentences.

- Literary Context. Gives a brief explanation to how this chapter fits into the broader text of Leviticus.

- Translation and Outline. Sklar provides his own translation and outline of the section crafted to show the text’s flow of thought.

- Structure and Literary Form. Summarizes how the author uses literary devices (e.g., key words, motifs, parallels, contrasts) to craft his message.

- Explanation of the Text. A thorough explanation on the use of words, phrases, and syntax in the biblical author’s message. Attention is given to how the material is arranged, what the biblical author is trying to say, and how he says it.

- Canonical and Practical Significance. This section tries to answer the question on what role does this book plays in the Bible’s canon.

- Sklar doesn’t let us down here either. Leviticus is a real head-scratcher when it comes to how it both resonates with the rest of the canon and applies to us today. Regarding Leviticus 10, the goal of God’s act of judgment are not merely for judgment’s sake or because he is ticked off. It is to prevent the furtherance of sin. When two of Israel’s priests, their spiritual leaders, rejected the King’s commands on how to approach him, the judgment needed to be especially severe. It showed Israel what would happen to them if they disregarded God’s kingship (and for that, read 2 Kings).

- Just like with out spiritual leaders today (Titus 1:7–8; 1 Tim 4:16), if the priests taught a warped picture of God, the people would have the wrong understanding of God’s merciful character, and they wouldn’t know what it meant to live out his commands properly. These priests were to instruct Israel on matters of purity and impurity, which would then help them to think through matters of moral purity and impurity. Matters of skin conditions and how they could infect others taught them visually how sin affects the community. Yet Israel’s leaders could not cleanse them of their impurities. They could only declare them either clean or unclean. Only God can actually cleanse of us our impurities, which leads us to the work of Christ, especially as seen in the book of Hebrews (9:14; 10:12–14).

Recommended?

As this review hopefully shows, I have really benefitted from Sklar’s commentary. Sklar has immersed himself in the Pentateuch for years, and it really shows throughout his commentary (see his work on Numbers and his shorter commentary on Leviticus). Whether you know Hebrew or not, pastors, teachers, or students will benefit greatly from this volume. This is an in-depth, evangelical study into one of the Old Testament’s most difficult, seemingly irrelevant books, and Sklar helps us to see the life that is in God’s word here. This commentary is highly recommended.

P.S., for more on Leviticus, Sklar has a supplementary volume on Amazon with all the information he couldn’t fit into this volume (which I reviewed here).

Buy it on Amazon or from Zondervan Academic

Other reviews in this series

- Judges — Boda/Conway

- Ezra–Nehemiah — Gary Conway

- Hosea — Jerry Hwang

- Joel — Joel Barker

- Obadiah — Daniel Block

- Jonah — Kevin Youngblood

- Nahum — Daniel Timmer

- Habakkuk — Kenneth Turner

- Malachi — Dennis Tucker

Lagniappe

- Series: Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament

- Author: Jay Sklar

- Hardcover: 835 pages

- Publisher: Zondervan Academic (January 12, 2021)

Disclosure: I received this book free from Zondervan. The opinions I have expressed are my own, and I was not required to write a positive review. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255 http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_03/16cfr255_03.html.

Amazon Affiliate Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.