The New Studies in Biblical Theology (NSBT) series is one that was pivotal in my theological education. While interning at a Bible College in England a friend of mine told me about this series. I asked IVP Academic for a few to review (see Rosner, Shead, and Beale), and the rest is history. This is the sixteenth volume I have reviewed, and it is a real joy to benefit so much from these volumes.

I am increasingly amazed that the boring books of the Bible are actually not as boring as I thought. In fact, the boring parts are often where the treasure is at. What piqued my interest in Ezra-Nehemiah originally was an article by Ray Lubeck about the problem of reading Ezra-Nehemiah. Initially, I found what he wrote compelling. It seemed that while Ezra and Nehemiah had the right heart motives, much of what they did was incorrect. But was it actually so? As I studied Ezra-Nehemiah (having reviewed three commentaries on these books), I have found myself agreeing less with Lubeck’s insights.

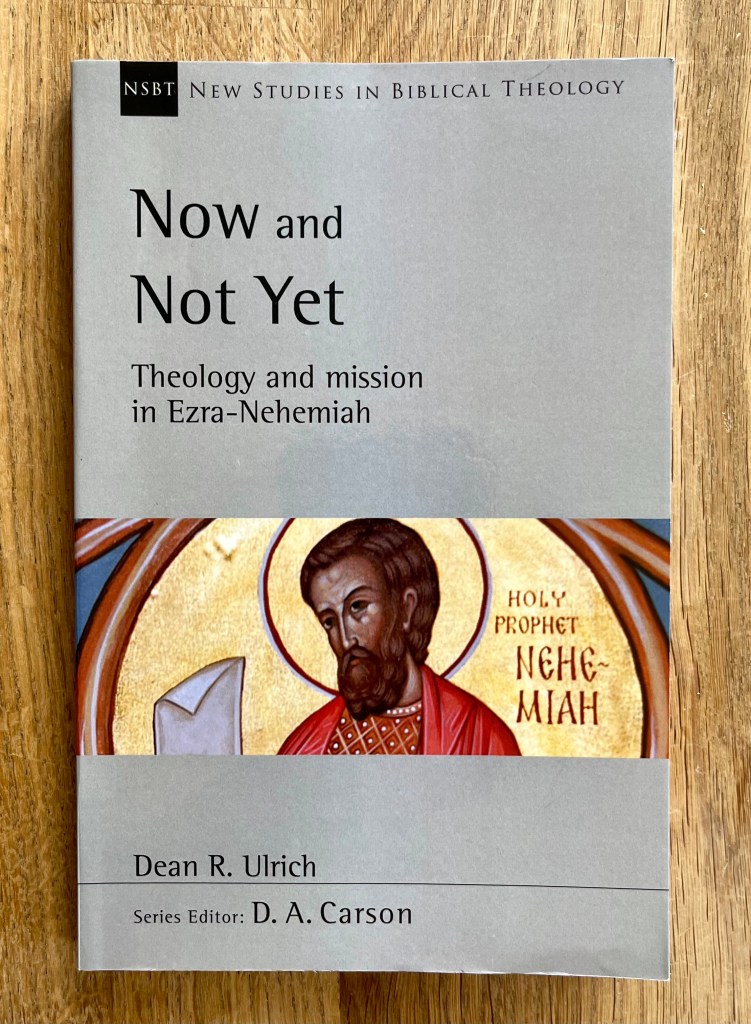

While I need to read Lubeck’s article again, Dena Ulrich has made a compelling case that Ezra-Nehemiah were, for the most part, in the right. (Nehemiah really should have skipped beating people and pulling their hair in Neh. 13.) Rather than focusing on leadership techniques like many teach from Nehemiah, Ulrich writes that these books focus “on how to be a godly participant in God’s story” (5). This volume focuses specifically on mission and the now and not yet aspect of these two books, (which according to Ulrich are only one book in the Hebrew Bible). The “now and not yet” is often thought to be a “New Testament thing,” but really the NT authors are just repeating what they learned from the OT.

Ulrich, seeing Ezra-Nehemiah as one book, divides it/them into three sections. These sections are separated by the same list of names that appears in Ezra 2 and Nehemiah 7:4–73a, occurring as a structural device that frames the second section:

- Ezra 1—Cyrus decrees the rebuilding of the Jerusalem temple.

- Ezra 3:1–Nehemiah 7:73a—The fulfillment of Cyrus’ decree.

- Stage one: The temple is rebuilt within twenty years, although not without much opposition (seemingly contra Isaiah 60).

- Stage two: Ezra returned “to rebuild the people” in the law of Moses so that they would live holy lives.

- Stage three: Nehemiah supervised the rebuilding of the wall.

- Nehemiah 7:73b–13:31—Celebrating the completed building project.

The Chocolate Milk

One thing I believe Ulrich did really, really well was application. He doesn’t pull Jesus out from under every stone. Instead he zooms out from his immediate discussion and places it within one of the threads running through the OT and into the NT. In Ezra 3:1–6, the returnees rebuilt the altar where God had chosen to place his name. This “was the first step towards worshipping God in accordance with Mosaic law, which was concerned with both the actions of the body and the attitude of the heart” (50).

Yet the post-exilic community experienced hostility from those who had been living in Judea during the exile. But instead of crippling the community, it drove them “to worship and entreat the Lord” (52). They were steeped in their Old Testament history and of God’s incredible acts of mercy and provision for his people. They knew “that God takes care of his people” (52). The application is that God never calls on us to rely on our own strength when trials come. We are to trust the Lord by obeying him and his commands “regardless of how counter-intuitive obedience may be” (52). Instead of striving by our own strength, we can use our strength, intellect, and resources for God’s glory as we trust his track record of trustworthiness.

Ezra 3:7 reminds us of Cyrus’ financial support. Ulrich points to other texts that speak of Gentiles who helped either with building the temple (i.e., King Hiram of Phoenicia, 1 Kgs 5:8–9) or with the tabernacle (i.e., Egyptian gifts, Exod 12:35–36). Isaiah 60:5–14 tells of gentile wealth flowing into post-exilic Jerusalem. The NT correlation is that Gentiles don’t help build a temple. They constitute part of God’s temple (1 Cor 3:16–17; 1 Pet 2:4–5).

Ulrich spreads his applications out throughout the whole book. I didn’t always appreciate how often application came up, yet at the same time I appreciated how smoothly Ulrich moved to applying such difficult texts—even the list of exiles in Ezra 2—to our lives. Pastors could learn from this on how to make the path to sermon application smooth.

Excluded Foreigners and Alien Wives

Excluded Foreigners

If Nehemiah 12 shows us the dedication of the wall and service at the temple, Nehemiah brings obedience to the law of Moses. Perhaps. Nehemiah 13:3 is tricky. Those who were there that day (does this include Ezra and Nehemiah, cf. 13:6?) read the law of Moses and found that it was written “that no Ammonite or Moabite should ever enter the assembly of God” (Neh 13:1). The people obeyed and separated from those with foreign descent. The question is, was this the correct thing to do?

Nehemiah 13:1 and 3 say, “And in it was found written that no Ammonite or Moabite should ever enter the assembly of God… As soon as the people heard the law, they separated from Israel all those of foreign descent.”

The questions to be asked are: Did they separate so as to remove these people from the temple, from inside the wall, from Jerusalem, or from the land? The events of the next paragraph (13:4–9) occurred “before this” (13:4), that is, at least before Nehemiah 12:1–13:3. 13:6 says Nehemiah wasn’t present for the events of 13:4–9. Were Ezra and Nehemiah then present for 13:1–3 (which actually occurred after 13:4–9)? Were the foreigners from whom the Judahites separated believers like Ruth or were they unbelievers? Did they expel only Ammonites and Moabites, or every foreigner? Some commentators like Gary Smith (my review) believe the community obeyed the law correctly.

Ulrich takes a more negative view here. He believes that those who excluded the foreigners in 13:3 forgot all about the foreigners who had been included into the community through their progression of faith “at the Passover after the completion of the temple’s foundation” (Ezra 6:21; cf. Neh 10:28; Exodus 12:43–49). I don’t know what I think right now, as I had only assumed that Nehemiah wasn’t there (13:6). I hadn’t noticed that he wasn’t there for the events that occurred prior in time (13:4–9). At first, Neh 13:1–3 seems unclear—yet is it really? I will need to study this more. Ulrich, makes a strong case.

Alien Wives

All commentators I have read regard the texts about the removal of the foreign wives and their children as tricky texts. Without getting too deep into this, Ulrich observes that the dismissed foreign women are called nasim nokriyôt (alien women). This term occurs nine times in Ezra-Nehemiah (Ezra 10:2, 10-11, 14, 17-18, 44; Neh. 13:26-27) but only one other time in the Hebrew Bible: 1 Kgs 11:1. In that context, the nasim nokriyôt clearly influenced King Solomon to depart from his covenantal responsibility of leading God’s people in faithfulness to God’s law (Deut. 17:14-20).

Ullrich writes,

It seems evident, then, that the nasim nokriyôt in Ezra-Nehemiah neither shared the covenantal community’s faith in Yahweh nor showed interest in embracing that faith. Their unbelief adversely affected a holy community, presumably by leading the husbands astray as the idolatry of Solomon’s wives had done to him (Neh. 13:26). Religion, not race, was the concern. (91)

Ulrich continues, “Ezra 6:21 and Nehemiah 10:28 (HB 10:29), in accordance with Exodus 12:43-49, make allowance for the conversion of foreigners and their participation in the covenantal community. It seems unjustified, then, to say that Ezra and the writer of Ezra-Nehemiah wished to exclude Gentiles as such from the covenantal community” (92).

Recommended?

Ulrich has produced a valuable volume on the often-overlooked books of Ezra and Nehemiah. While I don’t find these texts particularly exciting, Ulrich’s insights made the reading worthwhile. On the other hand, while the theme of mission and the “now and not yet” are threaded throughout his book, I think a final chapter highlighting these specific themes would have strengthened the book’s focus.

While other NSBT volumes typically show how the book revolves around a certain theme (see the volumes on Ruth, Acts, and Exodus), this was more like a wide-angled commentary on Ezra-Nehemiah with comments on mission and “now and not yet” spread throughout. While it didn’t impress me like many of the other volumes I’ve read, this one remains a beneficial resource on these neglected books. If I ever teach through Ezra-Nehemiah, this will certainly be by my side.

Buy it on Amazon or from IVP Academic

Other NSBT reviews can be found here.

Lagniappe

- Author: Dean R. Ulrich

- Paperback: 200 pages

- Publisher: IVP Academic (December 21, 2021)

Disclosure: I received this book free from IVP Academic. The opinions I have expressed are my own, and I was not required to write a positive review. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255 http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_03/16cfr255_03.html.

Amazon Affiliate Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.