Summary

Either/Or

The first two chapters offer competing ways to interpret the Bible’s use of the Bible.- Should interpreters keep the Testaments separate from each other or should they see them as connected? That is, a number of interpreters believe that the way the New Testament interprets the Old Testament is highly aligned with how the Second Temple Jewish Literature and the rabbis interpreted the Old Testament (cf. Michael Fishbane and Richard Longenecker). The authors of this book believe the Bible’s testaments are connected, and they show examples of how the Messiah’s own exegesis followed that of the Old Testament (the interrelationship of individuals and the collective, now and not yet fulfillment, typology).

- Is it acceptable for interpreters to adjust the meaning and/or adjust the context of the Scriptures or should they understand the reuse of Scripture as advancing revelation? The authors opt for the latter and show how the reuse of Scripture advances revelation (seen in the texts about a prophet like Moses, Exod 20:19; 33:11; Deut 4:34; 5:25–28; 18:15–18; 34:10–12). They offer good examples of the former and show how those kinds of interpretations are misguided.

- However, the authors don’t define what it means that scholars adjust meaning and/or adjust contexts “to try to fix the problem they [such scholars] sense with the way biblical authors interpret earlier scriptures” (24). Instead they just offer a bunch of varied examples of how some scholars don’t see how the reuse of Scripture advances revelation.

Both/And

Chapters three to six offer a both/and approach to these interpretive methods.- In chapter three, the authors believe that detecting allusions is both an art and a science.

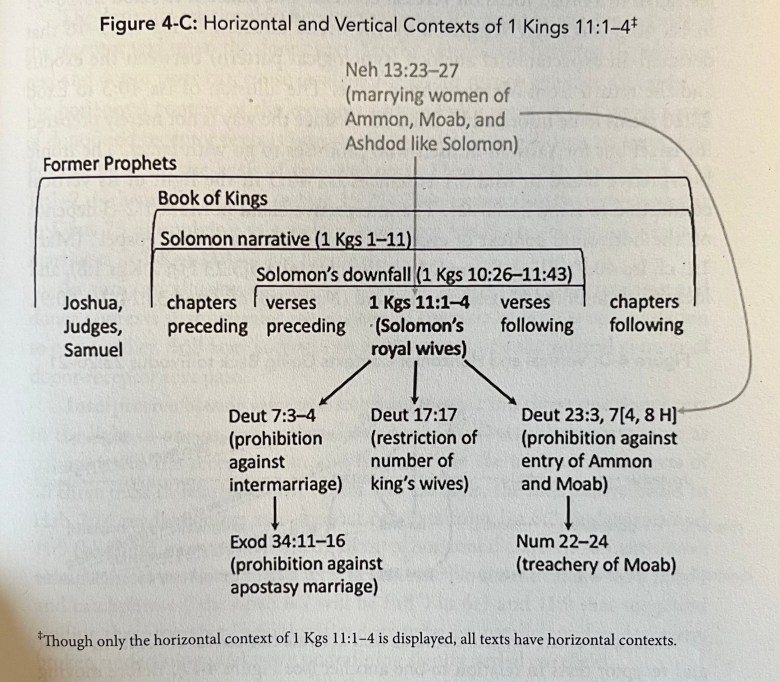

- In chapter four, the authors believe that we need to understand both the horizontal context of the donor text (the text being quoted) and the vertical context (all of the uses of that text, or that text’s donor text).

- In chapter five, the authors believe that we should prioritize the biblical relationships to a text without downplaying extrabiblical texts (such as Qumran literature).

- In chapter six, the authors believe that typology can be both backward-looking and forward-looking (though not at the same time).

- Chapter seven, oddly enough, is both an either/or and both/and chapter. That is to say, the choice is between either only historic exegesis or both historic exegesis and prosopological exegesis. This chapter was helpful, but it just didn’t click for me. I haven’t been convinced of prosopological exegesis yet. This chapter, while offering helpful critiques of Bates’ work and the “nonessential elements” he added to prosopological exegesis, didn’t really make prosopological exegesis any easier to understand.

The Spoiled Milks

One downside to this book is the jargon and that the language is often clunky. This is regrettable but understandable. Writing about “scriptural interpretation within Israel’s scriptures” can’t be reduced to anything shorter, nor can it be abbreviated. Some of these things just are clunky. But also, I was confused by what they meant by the phrase until, eventually, I realized they meant how the Old Testament authors used other Old Testament texts. I know variety is the spiace of life, but why not just say that? I found the first two chapters heavy to read. In a strange twist, by trying to keep these chapters succinct, I was often confused on what the authors meant. They offer good examples of other interpretations in which they disagree. But there is a lot of jargon that muddies the waters.The Chocolate Milk

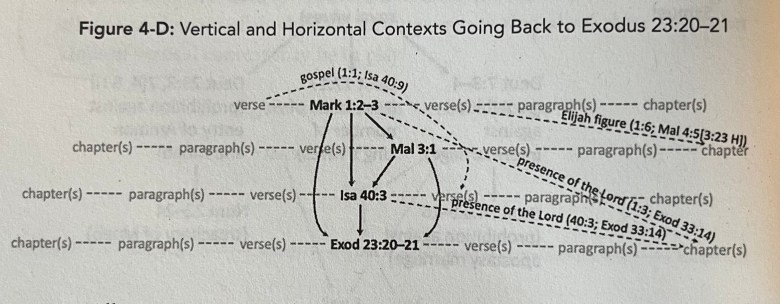

Despite all of the above, I highly appreciated the authors’ emphasis on how the two testaments are intimately connected. The New Testament authors faithfully interpreted the Old Testament, and Schnittjer and Harmon offer good and very detailed examples in the case studies at the end of each chapter. The authors distinguish typology from allegory and illustrations and show how you can tell (ch 6), they offer controls when searching for allusions, and they offer thicker readings of the text by showing how so many texts reuse earlier texts and theology. Throughout the book the authors give numerous examples to make their point, and the case studies bring those ideas together in order to examine a few specific texts. Here is an example of the vertical and horizontal context of Mark 1:2–3, which was the case study from chapter one (pp. 20–22). Although, I think the vertical context here could have gone one step further back. According to Jim Hamilton in his book Typology, Exodus 23:20–21 and the reference to God’s angel being sent before Moses and Israel alludes back to Genesis 24:7, where God will send his angel before Abraham’s servant in order for him to find a wife for Isaac.

Recommended?

Where without straying into odd conclusions

Buy it on Amazon or from Zondervan Academic! .

Lagniappe

- Author: Gary E. Schnittjer and Matthew S. Harmon

- Hardcover: 260 pages

- Publisher: Zondervan Academic (October 8, 2024)