“Test me in this,” says the LORD Almighty,

“and see if I will not throw open the floodgates of heaven

and pour out so much blessing

that there will not be room enough to store it.”

(Mal. 3:10)

W. Dennis Tucker—professor of Christian Scriptures at George W. Truett Theological Seminary—has contributed the newest volume (so far this year) to the excellent ZECOT series, and it, like all the others I have reviewed, is detailed and an excellent source of judicious exegesis. This series is adept at showing how discourse analysis helps us understand both the smaller () and the longer books of the Bible (Leviticus, Judges, Ezra-Nehemiah, Proverbs).

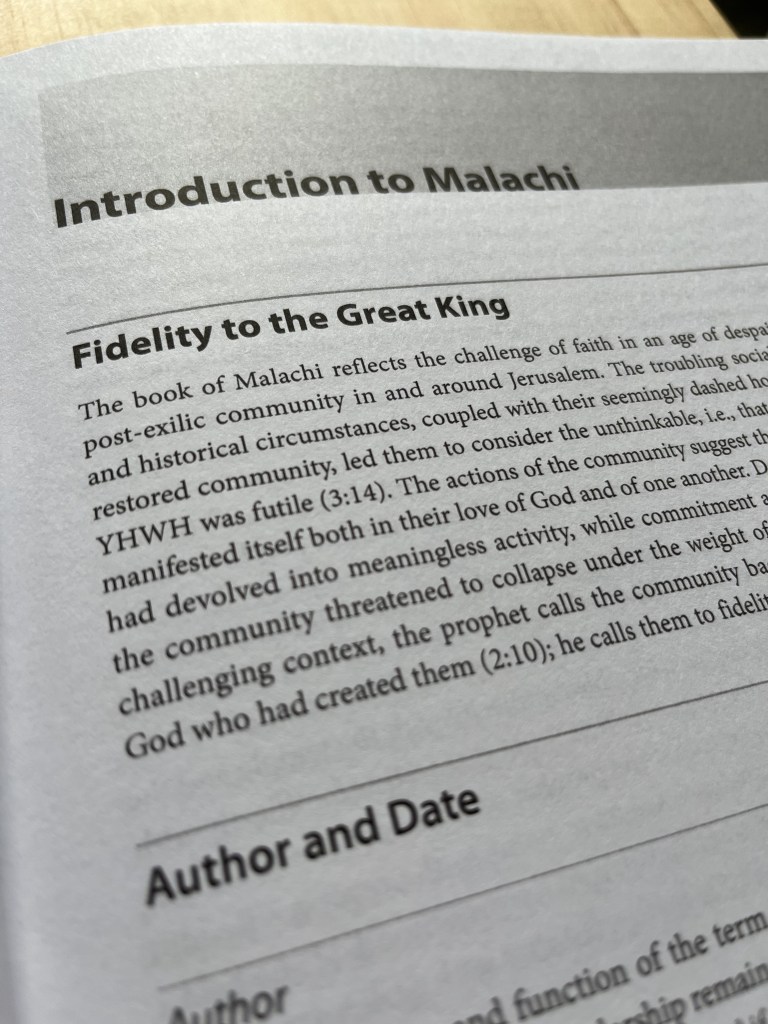

Many Christians are familiar with Malachi because it is the last book of the Old Testament (in English and the LXX), because Malachi ends talking about Elijah’s return seen later in John the Baptist in the Gospels, and because Malachi talks about tithing. But certainly there must be more to this prophetic book. According to Tucker, Malachi’s main theme is “fidelity to the great King” (5). Malachi aims to enger faithfulness through their hope in the great King who chose them to be in covenant with him. They are to be faithful to him, and through that faithful to each other.

By looking at some historical background, Tucker places Malachi as prophesying before Ezra and Nehemiah showed up on the scene. While the temple was completed in Ezra 6:15 (515 BC), there was a functional temple prior to that (Hag 1:12–15a, 520 BC). The primary problems that arise in the community arise not from baalism and other foreign gods, but from pragmatism. Through “[n]atural disasters (Hag 1:6), oppressive taxation (Neh 5:15), and economic and political corruption (Neh 5:7–8, 15),” many in the community began to believe that God was not on their side (105). This then reflected itself in how they worshiped God and treated each other: they no longer tithed (which would have helped the community), they married foreign wives for economic and political reasons (threatening the community’s unity and worship of God through worshiping other gods), began to divorce their own wives, and despised the name of the Lord.

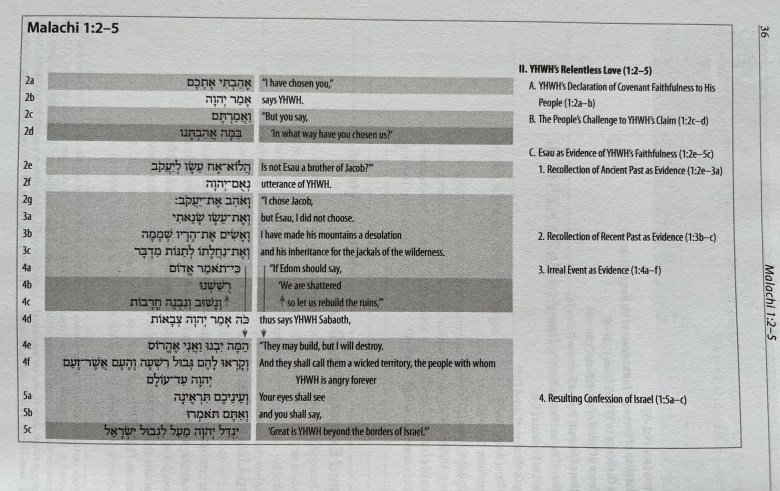

How do we work through this morass? Tucker uses analyzes Malachi’s rhetoric, how he structures his discourses, and how we can understand his intentions in what he said (and wrote). Tucker really dives in deep in the grammar, positioning of subjects and verbs within the Hebrew syntax to determine what Malachi believed was most important. He brings in many other scholars for insights, especially with ambiguous terms and verses, such as all of 2:15, as well as the title “sun of righteousness” in Mal 4:2.

Commentary Structure

Each chapter follows the same structural path:

- Main Idea of the Passage. The main points are condensed into 1-2 sentences.

- Literary Context. Gives an explanation to how this chapter fits into the broader text of Malachi.

- Translation and Outline. Tucker provides his own translation and outline of the section crafted to show the text’s flow of thought.

- Structure and Literary Form. Summarizes how Malachi uses literary devices (e.g., key words, motifs, shifts in personal pronouns, parallels, contrasts) to craft his message.

- Explanation of the Text. A thorough explanation on the use of words, phrases, and syntax in the biblical author’s message. Attention is given to how the material is arranged and how Malachi gets his message across.

- Canonical and Practical Significance. This section tries to answer the question on what role does Malachi plays in the Bible’s canon.

Tucker’s exegesis is shrewd and sensible, and he is careful not to accept simplistic answers. Regarding tithing, Tucker notes two kinds of reductionistic arguments. One line reasons that new covenant members are not under the law, so we don’t need to tithe. Others claim that the concept of tithing occurs repeatedly in the Old Testament and even shows up in Paul’s chapters on giving in 2 Cor 8–9. Rather, God has given us a picture “of a life rooted in trust, expressed in community, focused on the Other, and characterized by generosity” (147). The idea behind certain OT tithing texts like Deut 14:22–29 matches with what we see in 2 Cor 9:8, that those in Corinth would give to fellow believers in Jerusalem so that they “may share abundantly in every good work.” Tithing helps remove us from our hyper-individualistic shell and reminds us “that we belong to one another” and “that we have embraced the vision of a corporate life intended by God” (147).

Recommended?

Whether you know Hebrew or not, pastors and teachers will benefit greatly from this volume. Tucker dives deep into Malachi’s syntax without leaving us there. He uses Malachi’s rhetoric to show us his theology in God’s faithfulness to his covenant members. This is his love toward us, that he chose us. He is for us, and we have a responsibility to be faithful to him and to love his people. This commentary is highly recommended.

Buy it on Amazon or from Zondervan Academic!

Other ZECOT reviews

- Leviticus — Jay Sklar

- Judges — Boda/Conway

- Ezra–Nehemiah — Gary Conway

- Hosea — Jerry Hwang

- Joel — Joel Barker

- Obadiah — Daniel Block

- Jonah — Kevin Youngblood

- Nahum — Daniel Timmer

- Habakkuk — Kenneth Turner

Lagniappe

- Series: Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament

- Author: W. Dennis Tucker, Jr.

- Hardcover: 202 pages

- Publisher: Zondervan Academic (March 12, 2024)

Disclosure: I received this book free from Zondervan. The opinions I have expressed are my own, and I was not required to write a positive review. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255 http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_03/16cfr255_03.html.

Amazon Affiliate Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.