How long, Lord, must I call for help,

but you do not listen?

(Hab. 1:2)

Kenneth Turner—professor of Old Testament and biblical languages at Toccoa Falls College and co-author of the recommended The Manifold Beauty of Genesis One—has added a new volume to the excellent ZECOT series, and it is a good one (as are all of the ones I have reviewed). This series has proved to be adept at tackling the smaller books of the Bible (of which Habukkuk is the fourth shortest) through discourse analysis (DA). That said, DA is deft enough to handle the larger books too (Leviticus, Judges, Ezra-Nehemiah).

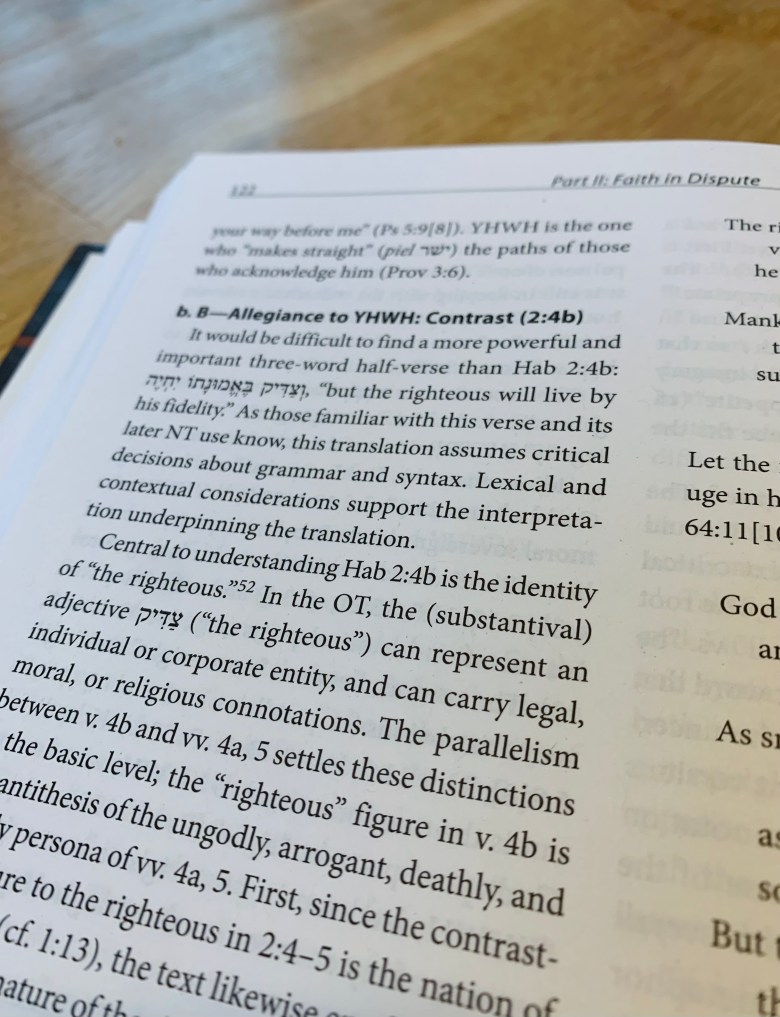

Many Christians are familiar with Habakkuk because Paul uses Hab. 2:4 in Romans 1:17 and Galatians 3:11, and probably because of the last few verses in Habakkuk where Habakkuk lays his trust in the Lord’s goodness and faithfulness (3:16–19). However, Turner writes that there are numerous hermeneutical challenges to Habakkuk. A number of words have flexible meanings (does emunah/pistis mean “faith,” “faithfulness,” or “fidelity”), different text traditions lie behind certain words, and Hebrews 10:37–38 uses Hab. 2:3–4 differently from how Paul uses it.

On top of that is the difficulty of Hebrew poetry. Habakkuk “is at the high end of denseness and sophistication of Hebrew poetry” (19). While OT scholarship is much further ahead in understanding DA for prose/narrative writings than it is for poetry, Tuner’s hope is that his commentary will contribute to the OT understanding of how DA works with poetic writing. Part of his methodology here is to establish poetic lines, determine the tense, aspect, and mood of verbs (not an easy task), and to compare English translations. While Turner hopes to contribute to the overall understanding of poetry DA, he admits that DA “runs the risk of imposing rigid structure and precise logic on a text that resists such” (23). Poetry is “deeply personal and emotionally charged,” and cannot simply be fit into a grid. Rather than giving the best-all-end-all of Habakkuk and poetry DA, Turner’s attempts at understanding Habakkuk’s structure are suggestions for readers to consider.

If you’ve read any of my reviews, you’ll know that the aim of this series is discourse analysis (also called macrosyntax). Discourse analysis is a tool used to understand the flow of thought. How words are built into clauses, clauses into sentences, and sentences into paragraphs which serve “as the basic unit of thought” (x). Ultimately it seeks then to understand how those paragraph ideas relate to one another within a whole book. Daniel Block, the general editor, writes that “too little attention has been paid to the biblical authors as rhetoricians, to their larger rhetorical and theological agendas, and especially to the means by which they tried to achieve their goals” (ix).

Outline

I. Superscription (1:1)

II. Faith in Dispute (1:2–2:20)

….II.1 Woeful Injustice in the Present (1:2–2:5)

….II.2 Woeful Justice in the Future (2:6–20)

III. Faith in Respite (3:1–19)

This is the same basic overall structure as what David Firth proposes.

Habakkuk is a prophetic text in a poetic dress. He was an official prophet of Yahweh who fits with the preexilic prophets. His message probably spans both before and after 605 BC when Babylon took for the first wave of exiles. Disagreeing with most commentators, Turner does not believe that there is any explicit rationale given for why the evil tyrant nation of Babylon is sent against Israel (p. 13, more on this below). However, that interpretation “is key to understanding the message of the book” (13).

The only person Habakkuk addresses in the entire book is God himself. Much of the spotlight is kept on Habakkuk’s personal struggle, one that “becomes a large part of the book’s overall message” (13). Turner believes that Habakkuk’s main message is about faith/faithfulness. Habakkuk struggles with understanding divine justice in light of Judah’s current immense sin and the impending arrival of the Babylon tyrant for seemingly no reason. Throughout the book, instead of giving up on God or his own calling, Habakkuk enters a process of transformation. He does “what God calls everyone to do: wait for and trust in the divine word and its fulfillment (2:3)” (p.14). A few key themes in Habakkuk are the character of YHWH, covenant theology, and anticipation of the NT gospel.

Turner’s sections on Structure and Literary Form are quite detailed, so you will find that plenty of fodder here. (Turner’s word count for these sections was originally four times as long! Those who want the full text can email him.) In these sections Turner considers the structure and pacing of the poetry, the expressions or verbal forms used, where and when parallelism is used (or is used incompletely), and more. Then the outline and genre is explained before explaining the text.

YHWH’s First Retort: The Power of Babylon (1:5–11)

After Habakkuk asks God how long he will allow the wicked to flourish, Yahweh responds by announcing “he will act—shockingly and inexplicably—by raising up a brutal, world-conquering, idolatrous nation” (58). He responds to Habakkuk, but he does not answer his question. In fact, he responds not to Habakkuk alone, but to a plural audience (seen in the Hebrew plural imperatives), which might possibly be the whole nation of Israel. YHWH calls “them to take a shocking look at the world (v. 5a), because YHWH is about to act in raising up the surging Chaldeans (vv. 5-6a)” (58).

Turner doesn’t believe that God actually answers Habakkuk’s question. As I wrote above, Turner does not believe God gives any explicit rationale given for why evil Babylon is sent against Israel. Representative of the other side of the argument, Ralph Smith wrote, “One is left to assume that the coming of the Chaldeans is to punish Judah for the evil described in 1:2-4” (WBC series). But the fact that Smith has to assume arises from the fact that Yahweh doesn’t give a reason for Babylon at all!

Smith’s remark makes Habakkuk sound like his contemporary Jeremiah, through whom God announced, “Look! I am bringing against you a nation [Babylon] from afar, O house of Israel” (Jer 5:15; cf. 6:22). Turner notes the differences between Habakkuk and Jeremiah:

Jer 5:11

For the house of Israel and the house of Judah

have been utterly treacherous to me,

declares the Lord…

15 Behold, I am bringing against you

a nation from afar, O house of Israel,

declares the Lord.

It is an enduring nation;

it is an ancient nation,

a nation whose language you do not know,

nor can you understand what they say.

Hab 1:13

You who are of purer eyes than to see evil

and cannot look at wrong,

why do you idly look at traitors

and remain silent when the wicked swallows up

the man more righteous than he?

In Jeremiah, God explicitly declares that because of Judah’s treachery (5:11, the same root occurs in Hab 1:13) and because of their refusal to heed earlier prophetic warnings (Jer 5:12-13), God will bring against them Babylon (v15). His judgment is “against you [i.e., Judah].” Turner directs us to the wider context of ”the covenant curses (see Deut 28:25, 36, 48-50, 63-65)” (p. 59). Yet this is not explicit in Habakkuk. If God was keeping his word to bring the covenant curses on a sinful and rebellious people, “why would the prophet continue to complain about God’s injustice (in Hab 1:12-17)”? (59). Instead, Turner believes that 1:5-11 (and vv. 14-17) “picture Babylon against the whole world, all of whom are seen as victims” (59). The answer, as 2:4 brings to us, is that the “righteous” person trust in God.

Canonical and Theological Significance

Along with the focus on a book’s overall message, I always appreciate the sections titled Canonical and Theological Significance. At the risk of being pedantic, Turner (as with all the contributors) shows parallel or contrasting thoughts with other texts in the canon and shows its theological significance. Regarding God’s seeming inconsistency (or aloofness to the wicked’s reign) in 1:5–11, Turner point directs our thoughts to Abraham’s challenge to Yahweh’s decision to destroy Sodom. Both question God’s justice: if he would “sweep away the righteous with the wicked” (Gen 18:23) or how he could tolerate the wicked (Hab 1:12–13).

YHWH, “seeing no need to justify himself,” does not answer either objection directly (94). In fact, “his responses to each are different” (94). Yahweh plays along with Abraham’s challenge, but he “only enlarges the amount of injustice that he will permit (Hab. 1:5–11). In each case, however, YHWH purposely and strategically allows his human servant to struggle and live in cognitive dissonance” (94). This cognitive dissonance does not bother Yahweh because side it leads to an eventual transformation of his servants.

God understands that we will struggle with the fact that he permits evil. He invites us to voice our questions (read the Psalms, Jeremiah, and Jeremiah). We should not challenge him, but we should continually reevaluate our thinking of God to make sure it is correct, orthodox, biblical.

Recommended?

Whether you know Hebrew or not, pastors, teachers, or students will benefit greatly from this volume. This is an in-depth, evangelical study into one of the Old Testament’s shortest, but still difficult, books. There is more going on in Habakkuk than the few verses most people hold on to (2:4; 3:16–19), but that doesn’t lessen their importance. Knowing the rest of Habakkuk’s context only works to increase the relevance of those verses. Turner holds his eye on both the tiny details and Habakkuk’s overarching ideas. This commentary is highly recommended.

Buy it on Amazon or from Zondervan Academic

Other reviews in this series

- Leviticus — Jay Sklar

- Judges — Boda/Conway

- Ezra–Nehemiah — Gary Conway

- Hosea — Jerry Hwang

- Joel — Joel Barker

- Obadiah — Daniel Block

- Jonah — Kevin Youngblood

- Nahum — Daniel Timmer

- Malachi — Dennis Tucker

Lagniappe

- Series: Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament

- Author: Kenneth J. Turner

- Hardcover: 304 pages

- Publisher: Zondervan Academic (October 3, 2023)

Disclosure: I received this book free from Zondervan. The opinions I have expressed are my own, and I was not required to write a positive review. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255 http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_03/16cfr255_03.html.

Amazon Affiliate Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.